About Zaha

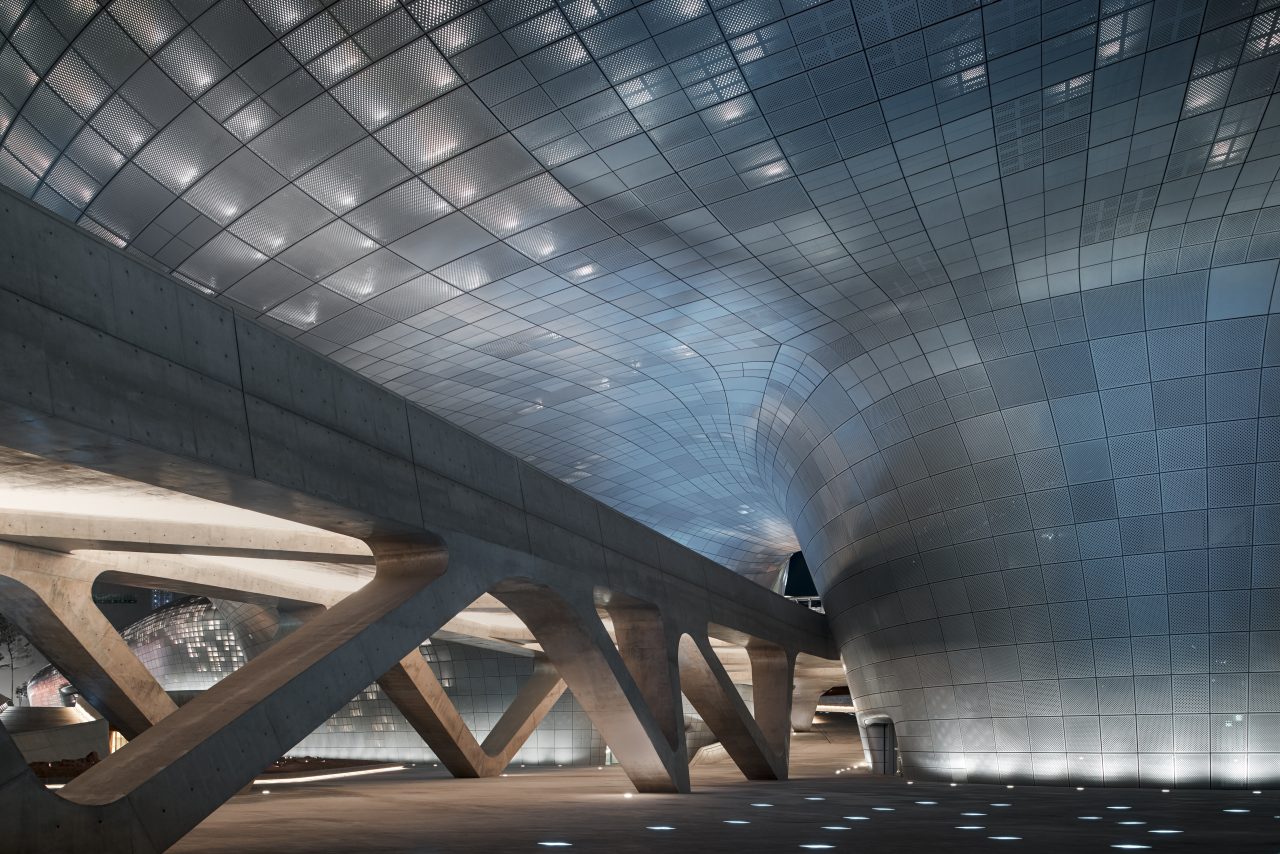

‘The ultimate ambition was to create fluid space, in every sense, between inside and out, and there is no boundary for people to move from one space to another.’ Zaha Hadid, 2012

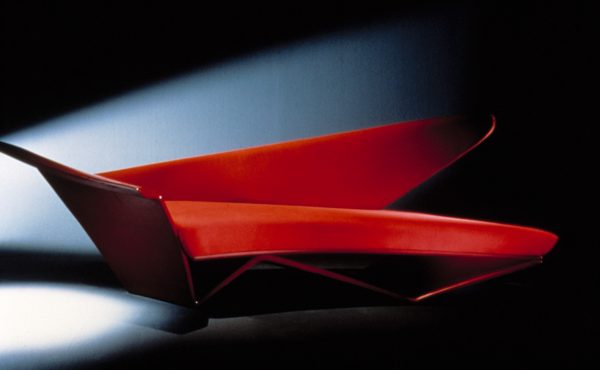

Zaha Hadid is globally recognised as one of the most important architects of the modern period and is frequently credited with developing an entirely new architectural language, in her quest for what she described as ‘complex, dynamic and fluid spaces.’ She consistently pushed the boundaries of what was thought possible in architecture, in a career encompassing design in all its forms, from urban planning to interiors and product design.

Zaha’s outstanding contribution to architecture and the arts was recognised during her life with numerous awards. She was the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize in 2004 and the first in her own right to receive the RIBA Royal Gold Medal in recognition of her lifetime’s work in 2015. She received the Stirling Prize in both 2010 and 2011, was appointed CBE in 2002 and made a Dame in 2012 for her services to architecture.

Zaha was born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1950, the daughter of Mohammad Hadid and Wajiha al-Sabunji. Her father was a leading liberal Iraqi politician and industrialist. She traveled widely with her parents as a child and education was central to her upbringing. She was educated at a religiously inclusive Catholic Convent school, led by a progressive headmistress who championed education for girls and invited university science professors to teach.

‘When I was growing up, mathematics was an everyday part of life, as well as drawing, or listening to music and reading books. My parents instilled in me a passion for discovery, and they never made a distinction between science and creativity…’

Zaha Hadid, May 2012.

Zaha’s early years coincided with a period of intense political and cultural change in her homeland and the development of a modern independent state in Iraq. During this time and over the next decade or more, Iraqi and Western modernist architects, including Rifat Chadirji, Frank Lloyd Wright, Gio Ponti, and Le Corbusier, were invited to develop buildings, monuments and schemes for a modern Baghdad.

‘As in so many places in the developing world at the time, there was an unbroken belief in progress and a great sense of optimism about the potential of constructing a better world.’

Zaha Hadid, 2004, Pritzker Prize Acceptance Speech.

In 1965, Zaha continued her education at boarding school in Switzerland and England, before studying mathematics at the American University in Beirut, Lebanon, between 1968-1971.

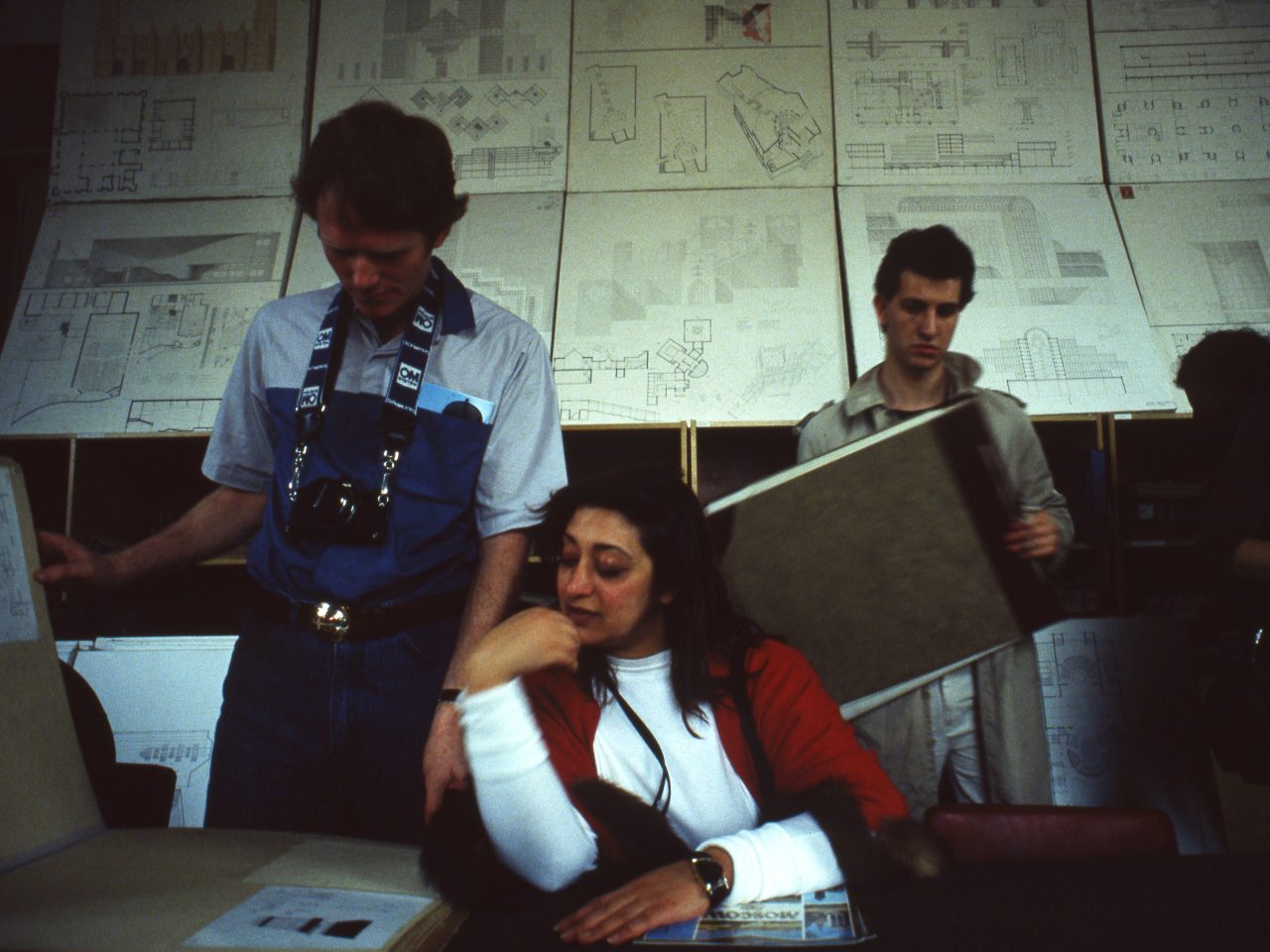

After moving to London from Beirut in 1972, Zaha soon enrolled to study architecture at the Architectural Association and was awarded the prestigious Diploma Prize in 1977. She was taught by Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, whom she went on to work with at the Office of Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) in London.

‘Zaha’s performance during the fourth and fifth years was like a rocket that took off slowly to describe a constantly accelerating trajectory. Now she is a PLANET in her own inimitable orbit. That status has its own rewards and difficulties: due to the flamboyance and intensity of her work, it will be impossible for her to have a conventional career.’

Rem Koolhaas, fifth year report at the Architectural Association, 1977.

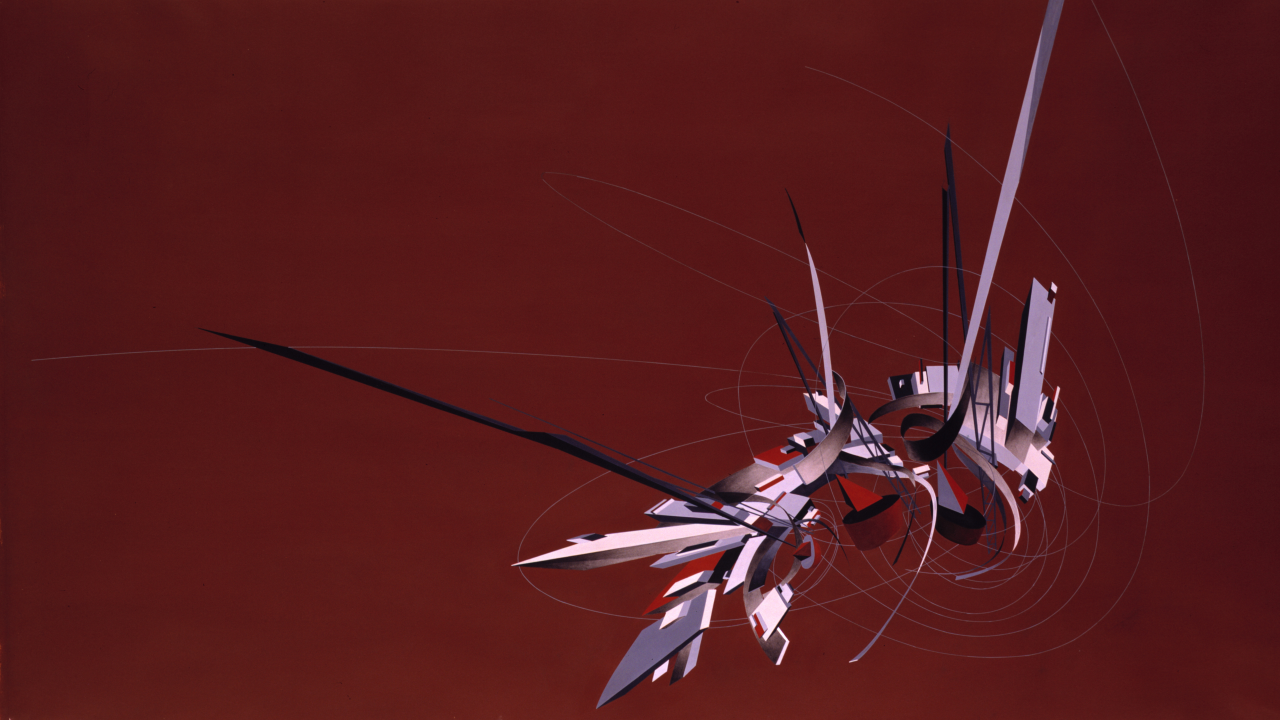

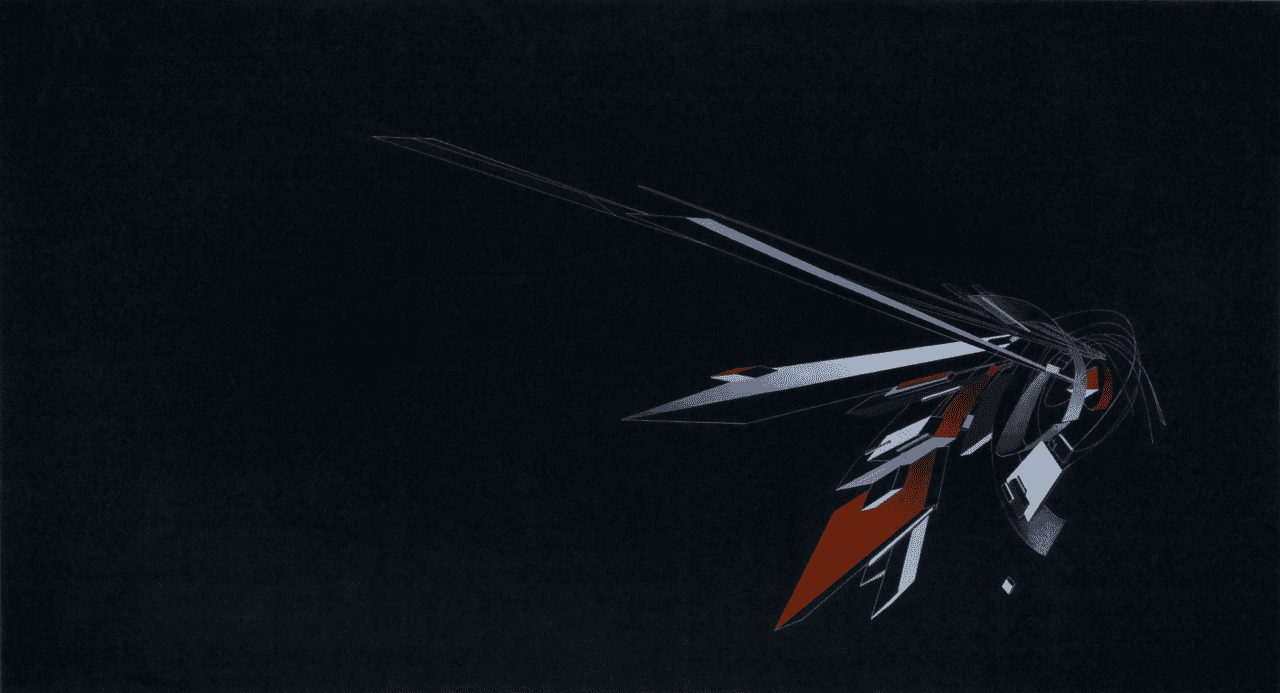

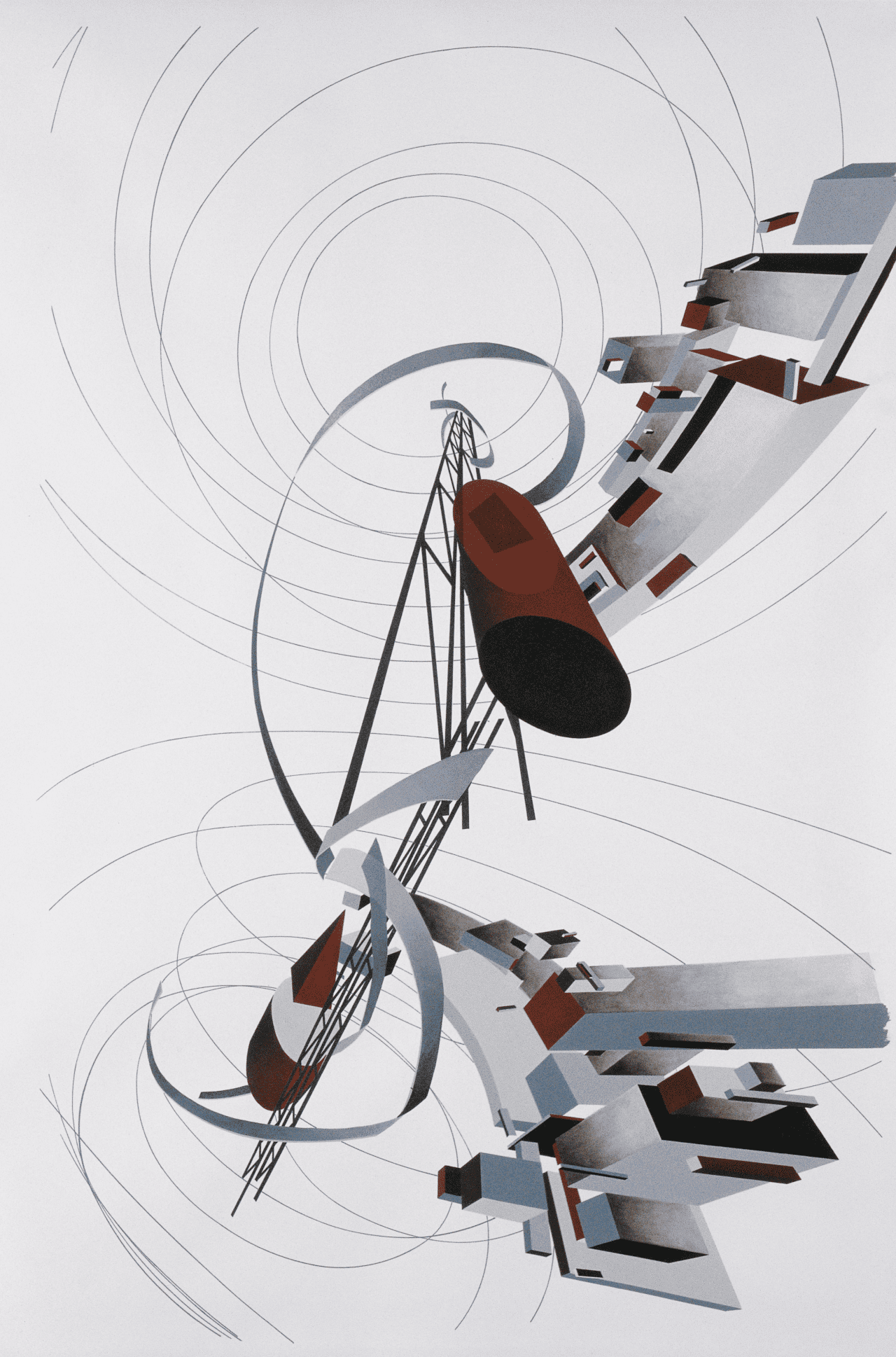

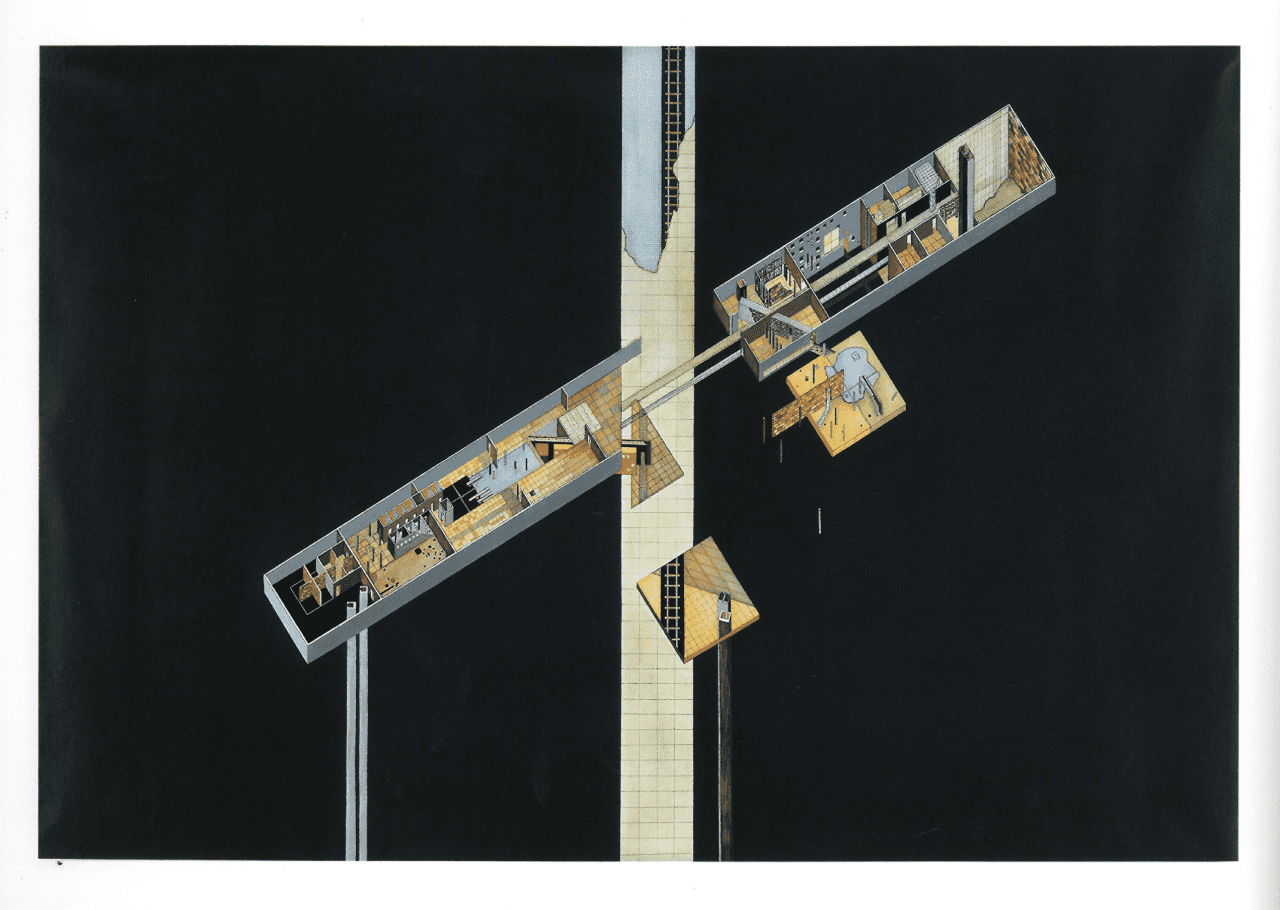

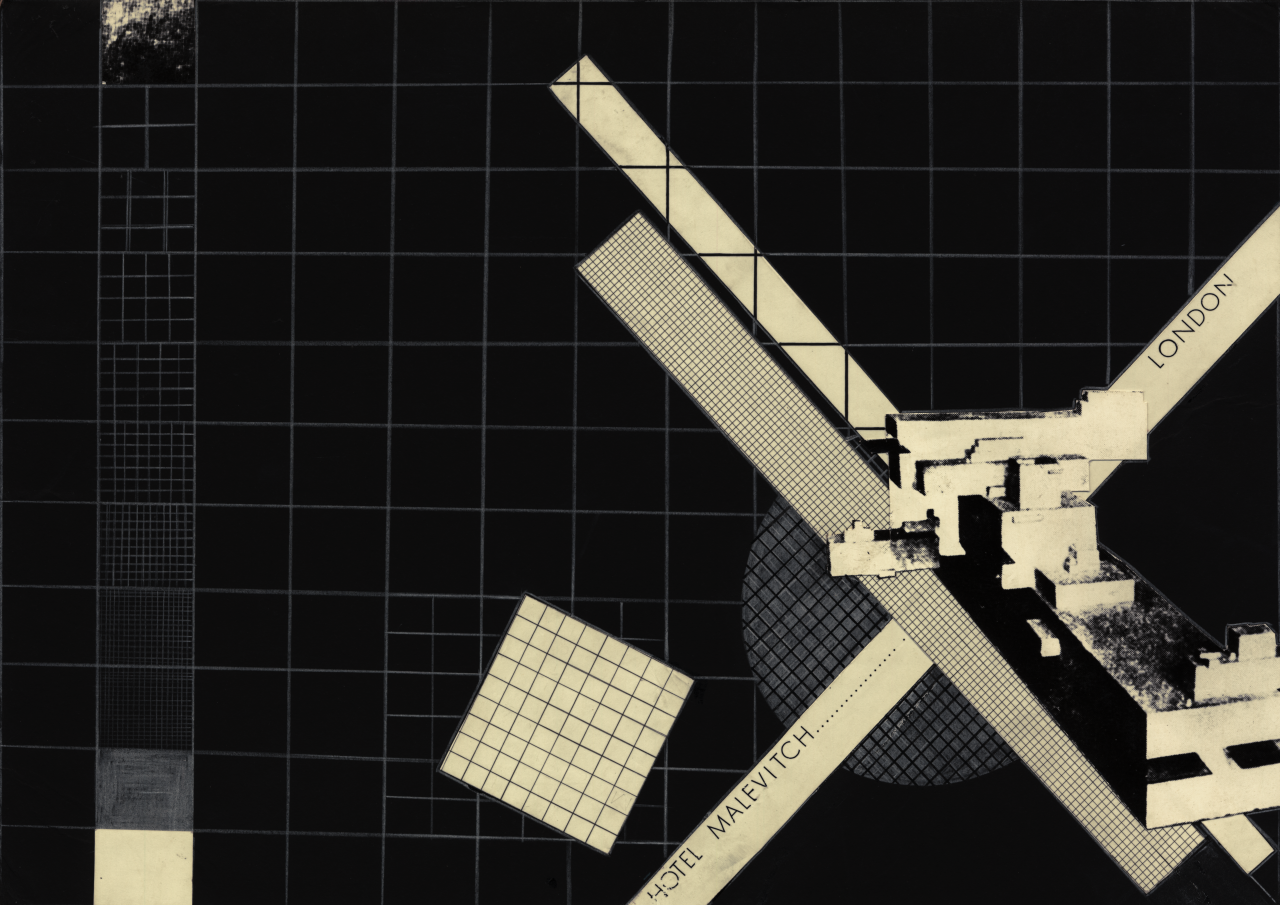

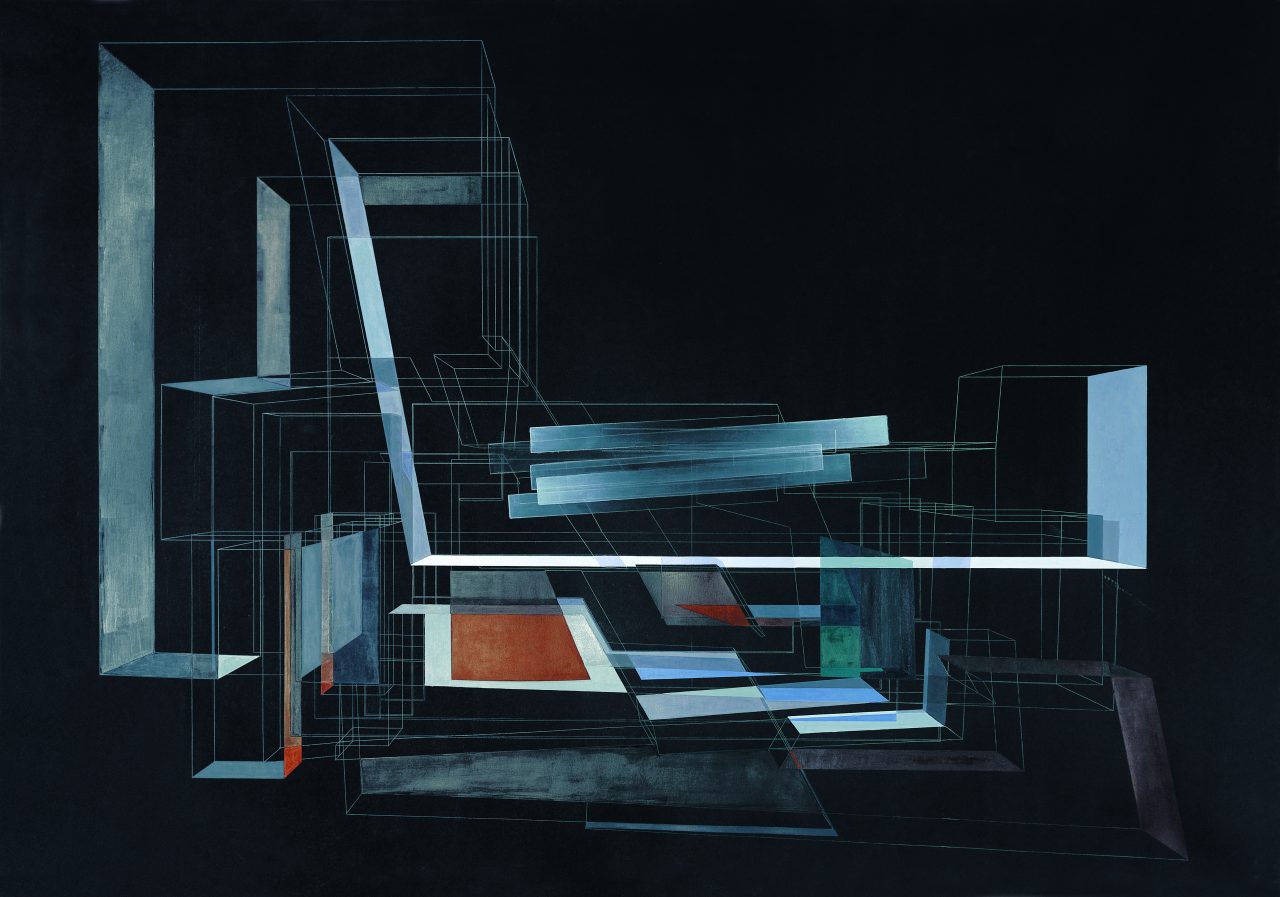

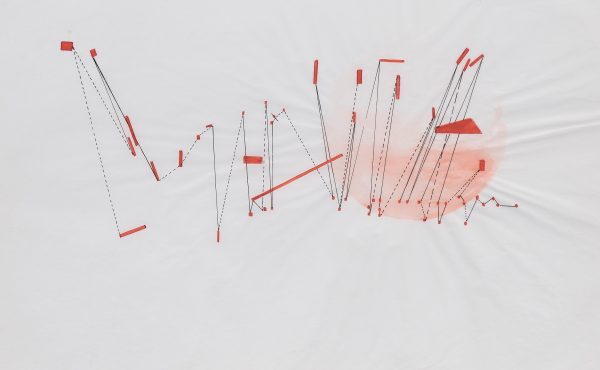

During her time as a student at the Architectural Association, Zaha’s work became shaped by her interest in the arts of the Russian avant-garde and she developed painterly techniques as an architectural design method.

‘The spirit of adventure to embrace the new and the incredible belief in the power of invention indeed attracted me to the Russian avant-garde… One concrete result of my fascination with Malevich, in particular, was that I took up painting as a design tool… I felt limited by the poverty of the traditional system of drawing in architecture and was searching for new means of representation.’

Zaha Hadid, Pritzker Prize Acceptance Speech, 2004.

In 1979, she founded her architectural practice from her small mews house in London.

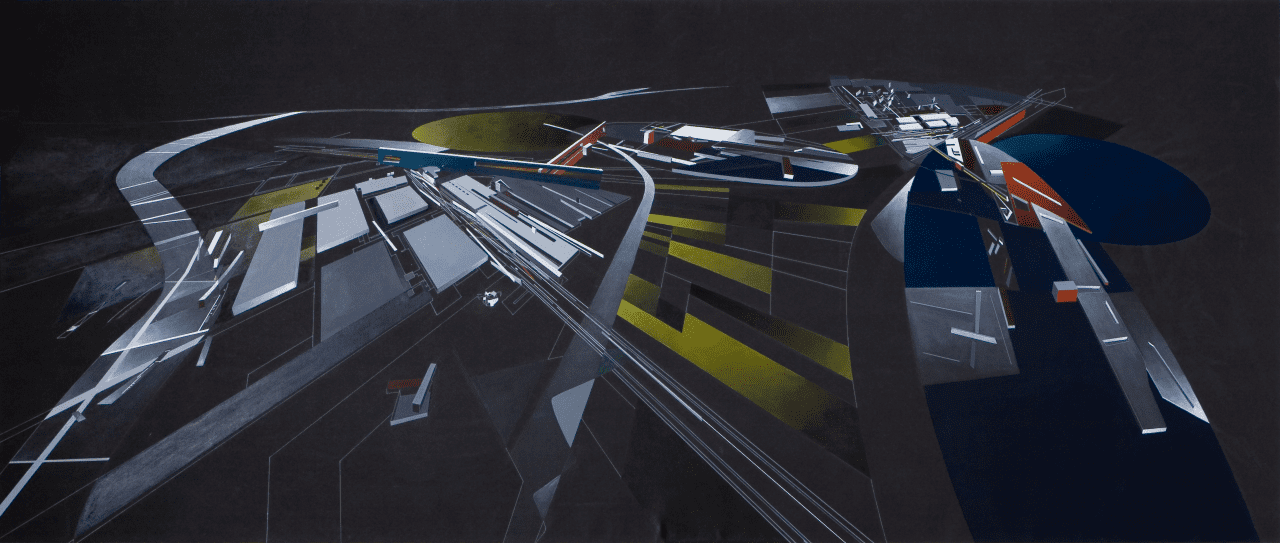

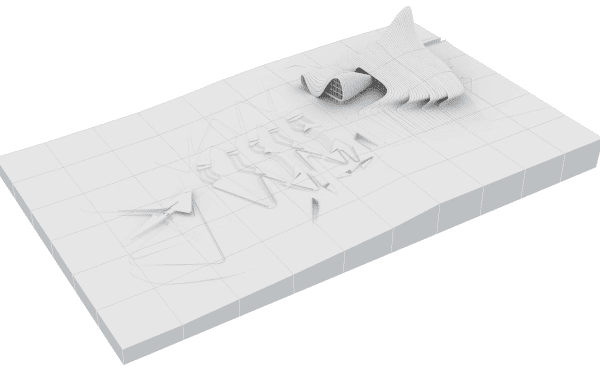

In 1983, Zaha won The Peak competition to design a leisure club in Hong Kong, China, gaining international recognition for her innovative approach to architecture and her unique representation of a flow of movement and dynamism through architectural drawings. The design was characterised by what she termed Suprematist geology, which incorporated themes of fragmentation, topography, infrastructural engineering, landscape and geometry. The Peak became ‘one of the 20th century’s most influential unbuilt projects.’ (Edwin Heathcote, 2016).

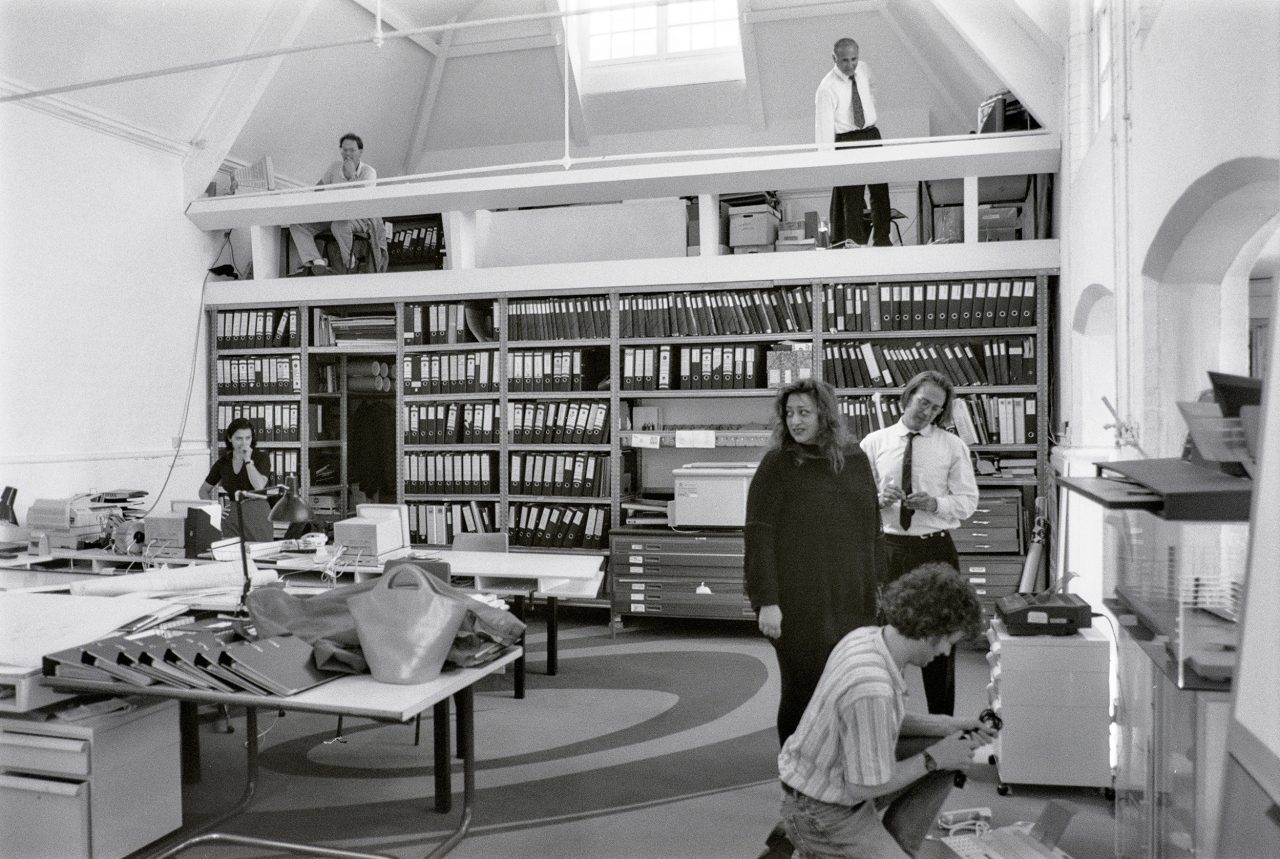

In 1985, Zaha rented a single classroom, referred to as Studio 9, in a converted Victorian school house in Clerkenwell, London, and ran her office from there. Eventually the office expanded to occupy the whole building.

In 1993, Zaha’s first building was realised, the Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein, Germany, commissioned by Rolf Fehlbaum, who said: ‘Zaha would have entered the history of architecture without ever building. She was an innovator before she ever built. But this, her first building, was a very strong manifestation of her fabulous talents.’

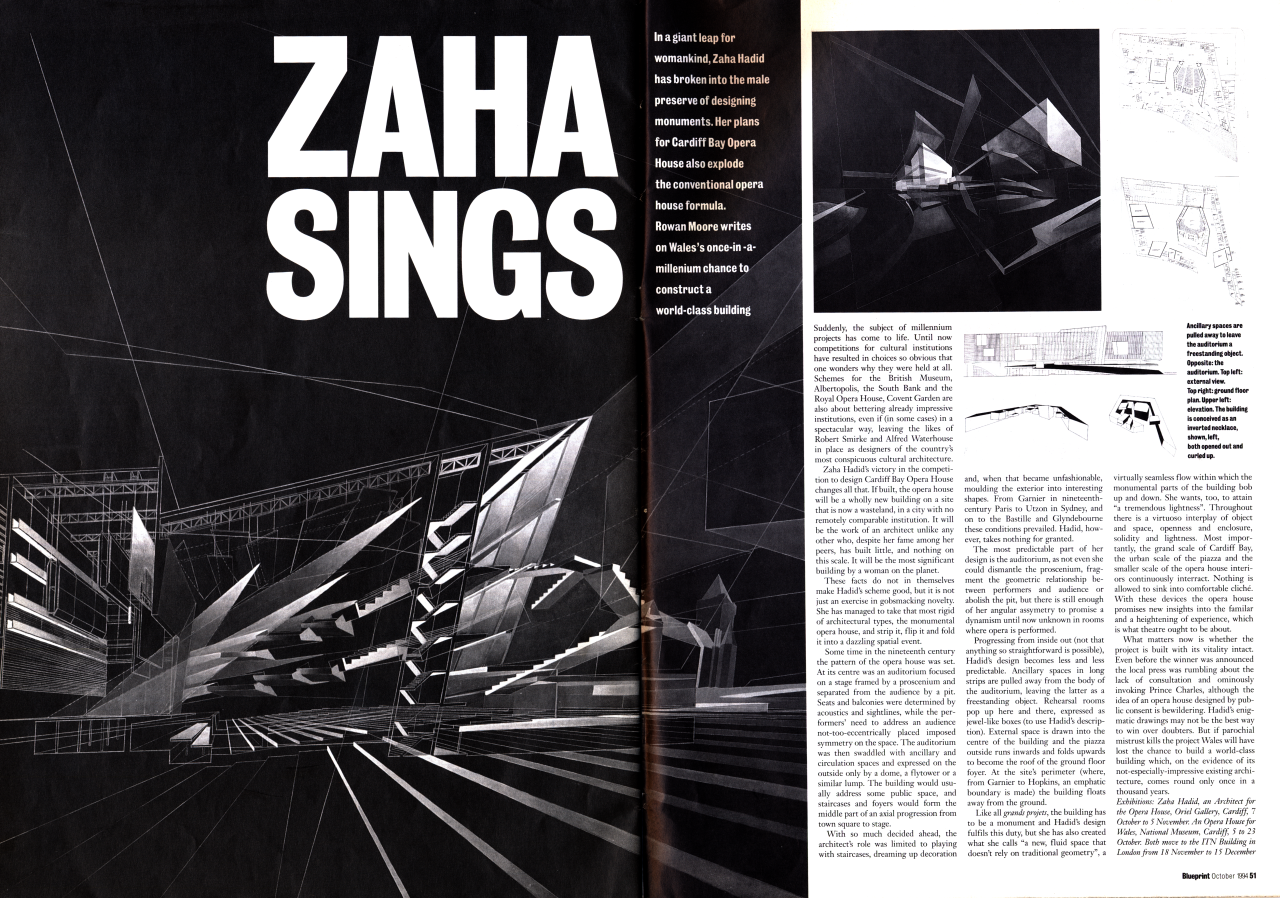

Following Vitra, Zaha entered a competition in 1994 to build the Cardiff Bay Opera House in Wales, UK, and won first prize. Despite winning first prize, she was obliged to re-compete for the project several times due to opposition and unfounded criticisms. Controversially, the project was never realised. The subsequent years became an intense period of research, experimentation and discovery for her practice, which prepared for the shifts in the status quo and creative boundaries of architectural design that her buildings went onto achieve.

The decade culminated in the commission to design the new Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, USA. Completed in 2003, the Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art won her the Pritzker Prize:

‘Zaha Hadid choreographs land, space, structure and person, so that each is inseparable from the other.’

Thomas J. Pritzker, 2004.

During her Pritzker Prize Acceptance speech Zaha said: ‘…one of my current preoccupations: the development of an organic language of architecture, based on these new tools, which allow us to integrate highly complex forms into a fluid and seamless whole’, an indication of the iconic seamlessness, flow and dynamism that became synonymous with her designs.

The years that followed witnessed the exponential growth of Zaha’s practice, with commissions such as the Bergisel Ski Jump (1999-2002), Innsbruck, Austria, Phaeno Science Center (2000-2005), Wolfsburg, Germany, Evelyn Grace Academy (2006-2010), London, UK, MAXXI Museum (1998-2009), Rome, Italy, London Aquatics Centre (2005-2011/14), London, UK, Heydar Aliyev Centre (2007-2012), Baku, Azerbaijan and Dongdaemun Design Plaza (2007-2014), Seoul, South Korea.

Zaha taught throughout her career, including at the Architectural Association until 1987, and held chairs and professorships at American universities such as Columbia, Harvard, Yale, and the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, Austria.

‘I think teaching is interesting because you discover things. I do think there should always be a connect between education and ideas and the profession, they should not be so alien to each other to exchange… I think the exchange is very crucial.’

Zaha Hadid, 2008.

This collaborative approach to architectural research and design was central to Zaha’s work and she credited the talent of her students (many of whom joined her practice), her architectural team, and the support and expertise of the engineers she worked with throughout her career. Their belief in her vision was hugely significant to her and supported her determination to realise a completely new architectural language.

‘She was somebody with a rare kind of courage’.

Rem Koolhaas, April 2016.

Zaha Hadid died in 2016, at the age of 65. At the time of her death, there were more than 400 people working for Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), which had worked on 950 projects in over 44 countries.